Admin note: These are excerpts from a larger research aimed at exploring aesthetic, socio-political and economic aspects the XVII century French formal garden of Versailles and understanding the reasons behind some of the contemporary responses to it.

“And the LORD God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.

And out of the ground made the LORD God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food […]

And the LORD God took the man, and put him into the Garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it.” (Genesis, 2:8, 2:9, 2:15)

How far have we come from the Garden of Eden? To what extent has our aesthetic sense changed? What did the XVII century French understand by the idea of garden and how do we respond to that today?

In the XVII century France, debates on the primacy of painting and sculpture were made from a geometrical point of view, introducing the spectator as the decisive third party, who was responsible for making the decision. The role of Vision, which had been holding metaphysical and epistemological primacy as the metaphor for knowledge, was now slowly undermined by new perspectives that related to Sensations and their relationship with Ideas.[1] In an article on social claims and the French garden, Chandra Mukerji endeavoured to demonstrate the existence of an important relationship between the material culture of the early modern era and the XVII century French formal garden.[2] Although history traditionally attributes court culture to a carefully organised elite system of style and taste, Mukerji’s anthropological approach demonstrates the important role the garden plays in the social, cultural and political life. The gardens such as those of Versailles must be seen as more than as a space of retreat and promenade, as architectural extensions than stand for royalty. One of the attributes that made the French garden exquisite is that it integrated diversity and form in geometrical, rational patterns. The recipe for a “perfect garden” consisted in finding new ways to use classical motifs and, at the same time, match the ambitions of the court and this is why Louis appointed André Le Nôtre as the court landscapist and engineer after seeing his work at Vaux-le-Vicomte.

Between André Le Nôtre’s birth, in 1613 and his death in 1700, the French formal garden would configure into its specific form. By this time, gardening had already been established as it came from a long tradition, and gardening had become an important art form, comparable with architecture or the visual arts.[3] Before Versailles, Le Nôtre made a name for himself as a parterre designer and caught the attention of the King after his work at Vaux-le-Vicomte, where he exquisitely manipulated levels and space.

Of all the elements in the Versailles gardens, Louis took official credit for only one: The Bosquet of the Three Fountains.[4] However, it is no secret that he was actively implicated and had full control over the shaping of the gardens. As the absolute monarch of a major player in European politics, Louis’s attributes expanded much towards foreign diplomacy. In these circumstances, the splendour at Versailles and its gardens had to engage in a competition with perfection; the display of an impressive collection of plants, lavish sculptures in marble and spectacular engineering water devices had to impress and to create the impression of limitless power. Even if ambassadors and other diplomats were – after the members of the royal court – the primary audience for the promenade in the park, the gardens were also an important site for the eyes of the wide public, which, Mukerji argues, is a significant contribution to them being treated as national assets and not private ones.[5]

The history of the garden is closely connected to the economy of collecting: the bigger the garden, the higher the demands for exotic, unusual and rare plants.[6] But the gardens were more than sites for collecting botanical specimens; they offered an occasion for collecting sculptures, building fountains (water was an essential part of the garden), grottoes or displaying exquisite items of furniture for outdoor dining. Indeed, in the XVII century Versailles, few specimens from the collection of plants have an individuality of their own, but were part of a rigorously planned medium, with which people could “display” information about the world they lived in.[7]

Even if Mukerji marginalizes the importance of the promenade, its role should, however, not be underestimated. The XVII century witnessed the development of the so-called “arte du promenade”[8]. The Cartesian theory states the role of the promenade causes, through the pleasures of the body, the elevation of the soul. The explanation behind mental activities such as sensation, memory, or imagination, can be find in formulating hypotheses about the interaction between the environment, the senses, and the processing of the brain.[9] Undoubtedly, this is something Le Nôtre must have had in mind when he designed the gardens at Versailles: the possibility of a promenade offers an opportunity for admiration, conversation and relaxation and the gardens definitely live up to that. Another important feature would have been alignment and disposition. As a mirroring of Tomaso Campanella’s La Città del Sole (The City of the Sun), the plans of Versailles were organized around the centre ( in the middle of the palace, which was the King’s Room) and vast avenues, metaphors for the Sun’s rays, starting from the Court d’honneur. As for the botanical collection, an artificial park, where everything is domesticated and integrated into geometric, controlled spaces guided by reason, it has been seen by some to exist only for the purposes of putting the statuary in value.[10]

****

Three centuries later, in 2008, Elena Geuna and Laurent Le Bon curated Jeff Koons’ retrospective in the palace and gardens of Versailles. Koons deliberately chose not to design new pieces for the exhibition, but to let the artwork choose the space of display.[11] The artist paid careful attention to the relationship between each art object and the space surrounding it, in an attempt to pay tribute to the immense artistic heritage from the Baroque era, and at the same time trying to find new ways for expressing contemporary ideas in the context of a historical site. Indeed, the artist’s intent is to establish a three-way relationship between the site, the contemporary artwork, and the public, in opposition to passive responses that are, in his opinion, the usual reaction when visiting a historical place. Moreover, he seeks to challenge the contemporaneity of historical monuments, which were themselves considered ‘contemporary’ at some point, and to ask questions about their relationship with the present.[12]

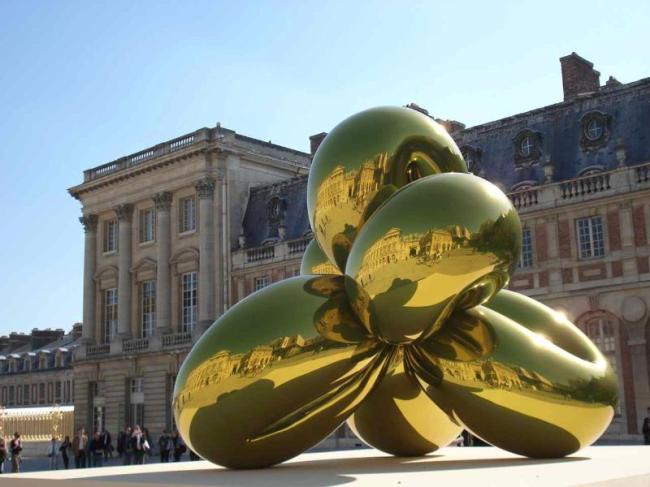

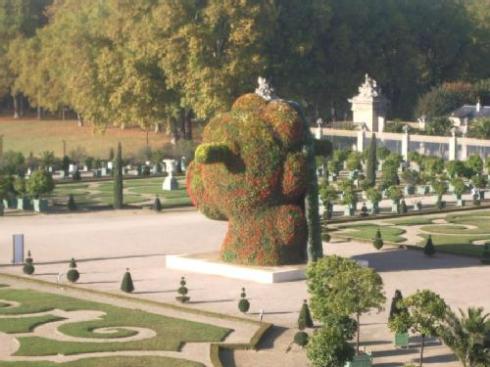

I wish to bring into discussion two of his works, namely the Balloon Flower and Puppy (Split Rocker). Both pieces were installed on outdoor premises, and both, although very different from one another, challenged the immediate surroundings. Koons changed the colour of the Balloon Flower,[13] aiming to integrate it into the palace’s golden decoration scheme, fresh, bright and reflecting the architectural features from around. The organic shape stands at the threshold between the depiction of vegetal motifs and the practice of twisting balloons, usually associated with childhood, beauty and innocence. Puppy, erected in the parterres of the Orangerie (the same place where Bernini’s sculpture once stood), with more than 90,000 petunias and geraniums planted in the pots for the duration of the exhibition, depicts a metamorphic creature, half-horse half-dinosaur.[14] The challenge was directed, this time, towards both the Sun King and Andrè Le Nôtre; Koons explores, again on a monumental scale, aspects of power, control and bringing fantasies to life, aspects that he believes, Louis XIV would have had access to: “Wherever the king moved the environment would change with him.”[15] The exhibition attracted a series of negative comments, ranging from aesthetic criticism to political accusations.[16]

To bring things further, Joan De Jean, in her article ‘The Chateau is Being Crowded Out’, argued that “Versailles’ decorating team—directed by royal painter, Charles Le Brun […]put together what would be called today a mixed-media installation. Each room’s décor combines a number of techniques: painting, bronzed stucco, plaster panels, gilt bronze, marbling, panels of patterned velvet, [and] panels of different-coloured marbles. The overall goal was never to create individual masterpieces that would have attracted attention away from the total effect. Le Brun intended instead to produce an ensemble that literally stopped visitors in their tracks and therefore served as instant proof that the Sun King was the wealthiest and most powerful ruler in Europe.”[17] The same rule applies to Le Nôtre’s gardens. Therefore, in terms of reception, a working theory could be that Bernini’s poignant style would single out the creation, not having blended with the rest of the garden sculptures and, implicitly, with the French taste. Afterwards, Berger argued that after its alteration, Louis might have decided to transfer the piece at the Lac du Suisses because then it would be “integral to the compositional scheme of the park.”[18] In different times, contemporary artists at Versailles (and Koons is not an exception) are doing exactly the opposite, in trying to single out a piece; for this they employ different concepts, different materials and propose a different type of dialogue. I am wondering, however, if the public’s strong reaction – such as that of the ‘group dedicated to artistic purity’ that protested outside Versailles’ gates prior to the Koons exhibition opening – is not combining the same mentality with a general prejudice against foreign art.

A year later, in 2009, Versailles hosted another contemporary art exhibition, this time by a French conceptual artist, Xavier Veilhan. Veilhan’s work blends and confronts the site at the same time; his symbols and ideas reflect a deep preoccupation for the numerous histories that Versailles witnessed. Interested in the orchestration of power and its iconographic materialization and using techniques borrowed from constructivist propaganda, Veilhan explores and transforms the visual ideology present in the gardens at Versailles.[19] By fabricating a map where he outlined the place the artworks will occupy and the route the visitor ought to follow,[20] Veilhan translated in cartography what The King had indicated more than three centuries before in his ‘Manière de Montrer Les Jardins de Versailles’. The intention behind works such as The Large Carriage or The Fountain point at the artist’s deep understanding of the Baroque relationship with equilibrium, scale and observation points. It is, indeed, with these two pieces, that Veilhan signals his preference for the palace’s ambulatory spaces and gardens and comes closest to the intentions Louis the XIV must have had. With The Carriage placed in the court d’honneur – coloured in purple, complementing the golden gate and the rooftop decorations – Veilhan brings forward perceptions of space and time by choosing to depict it in motion. A possible interpretation draws attention upon the passing of time as opposed to the durability and monumentality.

By working with stage designers,[21] the artist experimented with ideas related to theatre, bringing forward the idiosyncrasies of the stage and of theatricality in the French Baroque era. The Fountain pays clear homage to the XVII century fountains; Ramade suggested that its pronounced – but calculated – verticality is a tribute to Brâncuşi’s Endless Column.[22] The artist’s preference for courts and gardens extends beyond the spaces themselves, in the piece called the Light Machine, where technological advance makes possible a bird’s eye view documentation of Versailles gardens and representing it on a screen.[23]

At the same time, Veilhan confronts and challenges. The emblem of Louis XIV, the Sun, which is an integral part of Versailles, is being challenged in the work Veilhan chose to situate on the parterre in front of the Grand Canal. By using metal shaped like pins needles, and by ‘pinning’ them to the ground, to form the shape of the moon, the artist opposes the symbol of the night to the symbol of the day, which Louis, if we imagine him looking from the windows in his apartment, would not have missed. On the same note, The Giant/ Yuri Gagarin aims to lengthen and complement Louis XIV’s governing attribute: ambition. Built on a large scale (4 meters), the figure crystallizes the power of science development and the humankind’s constant aspiration to mastering the Universe. His position, his mission and the missing part of his chest, all point towards an allegory of the Fallen Man.[24] The Giant points definitively to the future; the ‘rocky’ texture and the colour could be seen as lunar metaphors – even if Gagarin did not walk on the moon, he was still the first human to see the Earth from the ‘outside’.

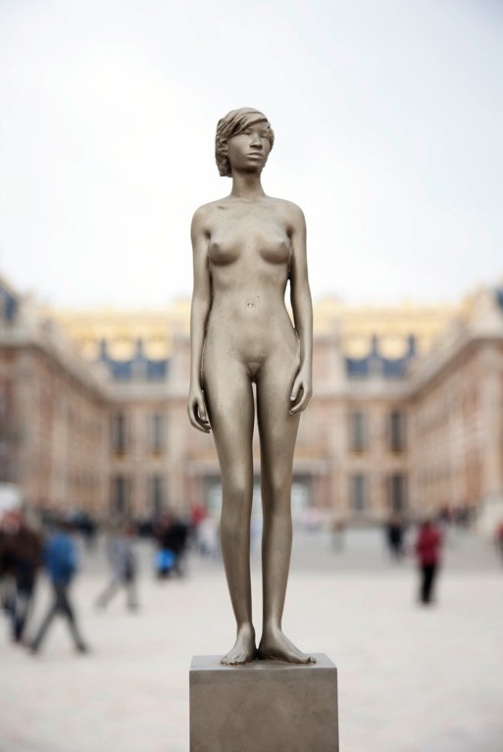

On the other hand, the anthropomorphic figures in The Naked Woman, The Architects or The Giant/ Yuri Gagarin subscribe to a different narrative. Save for the last, the figures are archetypal, allowing the viewer the possibility to project himself beyond the anecdotal.[25] The woman is a generic, almost primitive figure, short-haired, facing the golden entrance gate, stripped of her clothes and standing on a oversized pedestal. If the monumental is usually associated with massiveness, timelessness and public significance (in which Versailles excels, and which was also explored in Jeff Koons’ exhibition in the previous year), The Naked Woman is marked by anonymity and deliberate un-monumentality.[26] She could be anyone – from a member of the Royal Court, one of the King’s mistresses, tangled in and powerless against court intrigues, to a woman in service, a pawn on a gigantic chess table. Furthermore, her gender recalls the well-established social hierarchies between men and women at the time, and her bareness is a clear a visual indicator of this.[27] Even the pantheon displayed in The Architects follows the same generic pattern translated into monochromatic sculptures standing on what appears to be pedestals, suggested only by a few lines.[28] The subjective interpretation mixes with the generic, managing to impose an intimidating authority over the spectator.[29] By choosing to locate them in and around the Water Parterres, Veilhan re-enacted the practice of collecting of garden sculptures – instead of admiring mythological figures, the viewer admires 20th century architects, but the principle remains the same.

LIST OF IMAGES:

JEF KOONS

1. Balloon Flower

2. Puppy/ Split Rocker

XAVIER VEILHAN

1. The Large Carriage

2. The Fountain

3. The Naked Woman

4. The Giant / Yuri Gagarin

5. The Architects

Claude Parent

Richard Rogers

Sir Norman Foster

Renzo Piano

Tadao Ando

Jean Nouvel

Anne Lacaton & Jean-Philippe Vassal

Kazuyo Sejima

Philippe Bona & Elisabeth Lemercier

5. Moon Map

6. The Light Bulb

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Adams, William Howard, The French Garden 1500-1800, Scholar Press, London

Art21, Jeff Koons at Versailles, iTunes video online, 2:39, Art21 Blog, http://blog.art21.org/2009/10/30/jeff-koons-versailles/, 2009

Berger R W, Bernini’s Louis XIV Equestrian: A Closer Examination of Its Fortunes at Versailles, Art Bulletin 63, no. 2 (1981).

Hoptman Laura, Unmonumental: Going to Pieces in the 21st century, in Unmonumental: The Object in the 21st century, R. Flood et al (ed.), London; New York: Phaidon in association with New Museum, 2007

Christafis Angelique, King of kitsch invades Sun King’s palace, The Guardian, Tuesday 9 September 2008, accessible via http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/sep/09/art.france

Clarke Desmond, Descartes’s Theory of Mind, Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford University Press, 2003

Craig Fisher, Jeff Koons courts controversy — and photos of sculpture at Versailles, LA Times, 19 September 2008, accessible via: http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2008/09/jeff-koons-soli.html

Irvine Chris, Jeff Koons exhibition at Versailles draws criticism, The Telegraph, 10 of September 2008, accessible via: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/2774812/Jeff-Koons-exhibition-at-Versailles-draws-criticism.html

Jeff Koons: Celebration, A. Hrüsch (ed.), Ostifildern : Hatje Cantz Verlag ; Berlin : Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2008

Jeff Koons, F. Bonami (ed.), Chicago : Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago ; New Haven : in Association with Yale University Press, 2008

Le Dantec Denise, Quand le Roi Bâtissait Versailles et ses Jardins, Dalhousie French Studies, vol. 29 Jardins et Chateaux (Winter 1994).

Lichtenstein, Jacqueline. The Blind Spot : An Essay on the Relations between Painting and Sculpture in the Modern Age. trans. Chris Miller. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2008.

Mukerji Chandra, Reading and Writing with Nature: Social Claims and the French Formal Garden, Theory and Society, Vol. 19, No. 6 (Dec., 1990).

Murg Stephanie, Fun King Meets Sun King: Jeff Koons to Exhibit at Versailles, Unbeige, 21 December 2007, via: http://www.mediabistro.com/unbeige/fun-king-meets-sun-king-jeff-koons-to-exhibit-at-versailles_b4397

Pérouse de Montoclos Jean-Marie, Vaux-le-Vicomte, trans Judith Hayward, Paris : Scala Books, 2007

Sciolino Elaine, At Versailles, an invasion of American Art, NY Times, [n.d.], via: http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2008/09/11/arts/design/20080911_KOONS_SLIDESHOW_index.html

Szántó Catherine, Le promeneur dans le jardin : de la promenade considérée comme acte esthétique. Regard sur les jardins de Versailles. PhD diss., Université Paris VIII, 2009

The Art Newspaper, Issue 218, November 2010, published online: 15 November 2010, available via http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/The-chteaus-being-crowded-out/21847

Thompson Ian, The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, Andrè Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Gardens of Versailles, Bloomsbury, London, 2006

Veilhan Versailles: Xavier Veilhan at the Château de Versailles, exhibition brochure, © Château de Versailles 2009, presentation of the works by BÉNÉDICTE RAMADE

Versailles : Deux Siècles d’Histoire de l’Art, études et chroniques de Christian Baulez, Versailles : [Société des amis de Versailles], 2007

Versailles: Le Jardin Courtisan d’André Le Nôtre, Le quotidian La Montagne online, [pdf], accessed on 07 April 2013

Walton Guy, Louis XIV’s Versailles, The University of Chicago Press, 1986

Wittkower R., The Vicissitudes of a Dynastic Monument: Bernini’s Equestrian Statue of Louis XIV, in De Atribus Opuscula: Essays in Honour of Erwin Panofsky, M. Meiss (ed.), New York, 1961

http://www.veilhan-versailles.com/blog/ accessed May 1, 2013

http://www.veilhan.net/rubrique-1195/cible-1082.html, accessed May 1, 2013

http://www.jeffkoonsversailles.com/en/

[1] Jacqueline Lichtenstein,. The Blind Spot : An Essay on the Relations between Painting and Sculpture in the Modern Age. trans. Chris Miller. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2008.

[2] Chandra Mukerji, Reading and Writing with Nature: Social Claims and the French Formal Garden, Theory and Society, Vol. 19, No. 6 (Dec., 1990), pp. 651-679

[3] William Howard Adams, The French Garden 1500-1800, Scholar Press, London, 1979, p. 75

[4] Guy Walton, Louis XIV’s Versailles, The University of Chicago Press, 1986, p. 37. Walton also argues that from the artistic point of view, the needs of the King and the extended Royal family were the sole decision factors in the organisation of Versailles (p.38); this would automatically extend to the gardens and it cannot be entirely true. While the King had undisputable veto power over most matters, it has been clearly noted that the gardens had to serve many purposes and to satisfy different categories of audiences, elements which needed to be taken into consideration before making a decision related to design.

[5] Mukerji, p. 675

[6] Mukerji affirms that even though the preoccupation for cultivating the exotic and the rare is not new, the cultural and economical flow in which they subscribe undergoes an important change in these years. A broad collection implicates an impressive global reach, and at the same time tying the histories of culture with the histories of collecting that expanded along with the development of trade. (p. 654)

[7] Ibid, p. 655

[8] For a pertinent and a thorough exploration of the matter cf. Catherine Szántó, Le promeneur dans le jardin : de la promenade considérée comme acte esthétique. Regard sur les jardins de Versailles. PhD diss., Université Paris VIII, 2009

[9] Desmond Clarke, Descartes’s Theory of Mind, Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 1-35

[10] Cf. Denise Le Dantec, Quand le Roi Bâtissait Versailles et ses Jardins, Dalhousie French Studies, vol. 29 Jardins et Chateaux (Winter 1994), pp. 31-54 and

Versailles: Le Jardin Courtisan d’André Le Nôtre, Le quotidian La Montagne online, [pdf], accessed on 07 April 2013

[11] Presentation y the curators of the exhibition, information available via http://www.jeffkoonsversailles.com/en/ (accessed 25 April, 2013)

[12] Ibid.

[13] Originally, the Balloon Flower was magenta; part of the Celebration series, cf. the volumes Jeff Koons: Celebration, A. Hrüsch (ed.), Ostifildern : Hatje Cantz Verlag ; Berlin : Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2008 and Jeff Koons, F. Bonami (ed.), Chicago : Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago ; New Haven : in Association with Yale University Press, 2008

[15] Art21, Jeff Koons at Versailles, iTunes video online, 2:39, Art21 Blog, http://blog.art21.org/2009/10/30/jeff-koons-versailles/, 2009

[16] In the English-speaking press and art blogs:

Stephanie Murg, Fun King Meets Sun King: Jeff Koons to Exhibit at Versailles, Unbeige, 21 December 2007, via: http://www.mediabistro.com/unbeige/fun-king-meets-sun-king-jeff-koons-to-exhibit-at-versailles_b4397

Angelique Christafis, King of kitsch invades Sun King’s palace, The Guardian, Tuesday 9 September 2008, accessible via http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/sep/09/art.france

Chris Irvine, Jeff Koons exhibition at Versailles draws criticism, The Telegraph, 10 of September 2008, accessible via: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/2774812/Jeff-Koons-exhibition-at-Versailles-draws-criticism.html

Craig Fisher, Jeff Koons courts controversy — and photos of sculpture at Versailles, LA Times, 19 September 2008, accessible via: http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2008/09/jeff-koons-soli.html

Elaine Sciolino, At Versailles, an invasion of American Art, NY Times, [n.d.], via: http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2008/09/11/arts/design/20080911_KOONS_SLIDESHOW_index.html

[17] The Art Newspaper, Issue 218, November 2010, published online: 15 November 2010. The article is available via http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/The-chteaus-being-crowded-out/21847

[18] Berger, p. 248

[19] Veilhan’s work, http://www.veilhan.net/rubrique-1195/cible-1082.html (accessed May 1, 2013).

[20] Veilhan Versailles: Xavier Veilhan at the Château de Versailles, exhibition brochure, © Château de Versailles 2009, presentation of the works by BÉNÉDICTE RAMADE, p. 3

[21] A very useful tool documenting the process of organising and curating the Versailles exhibition can be found via: http://www.veilhan-versailles.com/blog/ (accessed April 3, 2013).

[22] Veilhan Versailles, p. 4

[23] Cf. Ibid, p. 4

[24] Veilhan Versailles, p. 3

[25] Veilhan’s work, http://www.veilhan.net/rubrique-1195/cible-1082.html (accessed May 1, 2013).

[26] In this context, un-monumentality is used to describe a kind of sculpture that is not against the values of monumentality (anti-monumental), but intellectually lacks them. For an in-depth exploration of the concept in 21st century sculpture, cf. Laura Hoptman’s essay Unmonumental: Going to Pieces in the 21st century, in Unmonumental: The Object in the 21st century, R. Flood et al (ed.), London; New York: Phaidon in association with New Museum, 2007, pp. 128-140.

[27] In his editorial, Ramade affirms that: “Here, like a new standard-meter, the female figure regulates the court’s balance. Its pathetic size, in comparison to the architectural ensemble’s affirmation of power acts to normalize; the woman, in her ingenious nudity, regulates the universe of Versailles.” It is true that her presence adds the human factor into the vast architectural space. However, in admiring her on top of a tall pedestal, the viewer might find identification difficult. His vantage point remains unchanged, which makes it almost impossible to relate it realistically to the immense space around. I believe that The Naked Woman should be viewed as a socio-political statement and as Veilhan’s attempt to create a slippage between what is conventionally thought of to be monumental and un-monumental.

[28] The archetype becomes here a catalyst that gives way to a reflection on the commemorative dimension of public statuary and on its action as a sign in our urban everyday life.

[29] In his anthropomorphic figures, Veilhan denies the viewer any real identification of and with a character: “More recently they have been given names, but there is nothing to indicate portrait as such. Even when I assembled my personal pantheon of 20th century builders, I named my monochrome sculptures, The Architects” (cf. artist’s homepage, http://www.veilhan.net/rubrique-1195/cible-1082.html, accessed May 1, 2013). The way I see it, identification is essential in works such as The Architects or The Giant, because Veilhan chose to attribute each sculpture to a historical figure: it is, after all, the key principle of the modern meaning of a pantheon.

1 Trackback or Pingback for this entry:

[…] Contemporary Art in the Gardens of Versailles: The Politics of an Eulogy (artperuses.wordpress.com) […]